20 Films That Celebrated Major Anniversaries in 2025

Blowing out candles for older releases

New year, same obsessions.

2026 is laden with upcoming releases that have cinephiles impatiently waiting like a dog that knows the meaning of “outside”. But January can be painfully slow, and it takes a while to dissociate from the year preceding it. In other words, it’s the ideal time to look back at 2025 and reflect on older films that hit historical milestones last year. After all, having a birthday pass by unacknowledged is a punishment that none of the films on this list deserve.

For the sake of discipline, this list excludes Barry Lyndon (1975) and Diabolique (1955), both of which the author has praised elsewhere, and The Ceremony (1995), which will have its own dedicated essay on Punished for Sincerity soon.

Without any further ado, here are 20 great films that celebrated big anniversaries last year.

Xala

1975, Ousmane Sembène, Senegal, 50th Anniversary

Few filmmakers can balance anti-colonialism and self-criticism with the same rigour as Sembène, known by many as the “father of African cinema”. And even fewer can accomplish such topical symmetry while making films that are this hilarious. Here, mockery and accusation meet, and from their firm handshake a ludicrous concept is born, in which an entrepreneur’s erectile dysfunction acts as a metaphor for the unscrupulous incompetence of Senegal’s national bourgeoisie. Sembène has plenty to say about a vast array of matters, from patriarchal polygamy to internalised oppression, and conveys it through dialogue exchanges that are as insightful as they are amusing. Lead actor Thierno Leye is stellar at playing an icon of capitalistic avarice and cultural self-rejection. If Frantz Fanon had the chance to watch the hysterical conclusion of Xala, he’d likely agree it has therapeutic value.

Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles

1975, Chantal Akerman, Belgium, France, 50th Anniversary

Akerman’s now duly recognised 3-hour masterpiece exposes the disquieting and unspoken nature of female labour, portrayed with the industrial consistency of a Fordist factory. Though the role of Jeanne can be misinterpreted as minimalistic, Delphine Seyrig’s performance is career-defining - which in itself is rather impressive, given the quality of her filmography. Time and space turn into political tools to study the relationship between gender roles and labour exploitation, as the Belgian filmmaker demonstrates how men appropriate the fruits of Jeanne’s labour power. No gargantuan call to adventure awaits her - only the next day, and the day after that. Small divergences in the mundane, like a coffee that tastes bitter no matter what or a light that the protagonist forgets to switch off, are enough to recalibrate the audience’s emotional response and beget concern for the character’s unravelling mental state. Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles remains one of the most sophisticated explorations of gender dynamics in all of cinema.

The Cave of the Yellow Dog

2005, Byambasuren Davaa, Mongolia, 20th Anniversary

Mongolian cinema often distances itself from the urban novelties of its capital, Ulaanbaatar, and turns its gaze to those preserving their pastoral customs in the steppes. Davaa, who also directed the fabulous Veins of the World, is one of the country’s most prolific filmmakers, and devoted much of her career to celebrating the nomadic cultures threatened by mining companies, climate change and modernity as a whole. Her magnum opus, The Cave of the Yellow Dog, follows Nansal, an adorable little girl who lives with her family and their livestock, and one day brings home a stray puppy. It’s a film about change, and how to welcome it, if at all. Though encased in the shell of an unassuming slice of life story, Davaa’s film, with its verdant hills and dangerous wolves, encapsulates the spiritual dichotomies between humans and nature, as well as death and rebirth. The ending alone makes this one of the most heartwarming films of the 2000s.

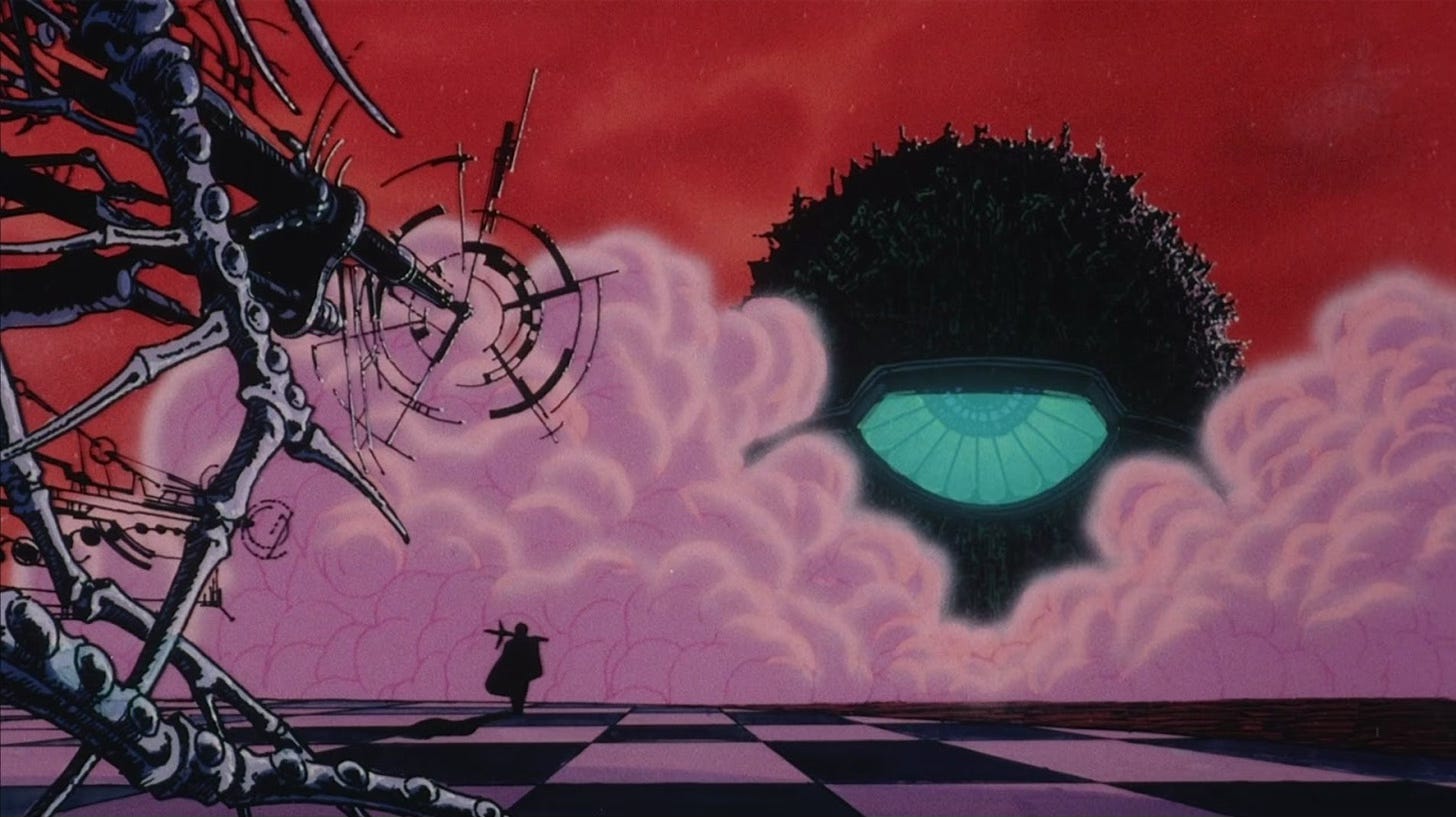

Angel’s Egg

1985, Mamoru Oshii, Japan, 40th Anniversary

A direct-to-video sci-fi anime about a nameless little girl and her mysterious egg. This cult classic is a fascinating investigation of faith and doubt. To unbelievers, the concepts of knowing and believing are strictly linked, but to God and His devoted children, the value of faith lies precisely in the hardship that it entails. Oshii’s story perfectly examines the dynamics between a little girl who believes in what she can’t see and an older skeptical boy hardened by a somber world that desperately needs God’s love. It’s a film about the journey of those who love God even if they are unable to feel His touch, and the loneliness of those who must prove that God isn’t there at all. Mandatory for animation lovers, and a great pick for agnostic cinephiles.

BloodSisters: Leather, Dykes and Sadomasochism

1995, Michelle Handelman, USA, 30th Anniversary

This documentary ventures into the BDSM lesbian leather scene in San Francisco. From DIY toy masterclasses to intergenerational beauty pageants, BloodSisters frames it all in detail - the needle play, the taped pliers, the mummification kinks. There’s a great speech towards the end that typifies the death drive - the speaker narrates the day in which a sub offered her own life as a gift, and talks about her temptation to take it. That’s only one of the many passages that explore sapphic pleasure at its rawest, demonstrating how sex that is often perceived as “dangerous” brings communities together in places where they feel the safest. Handelman platforms voices worth listening to in a film that makes great use of its limited budget. BloodSisters still shocks prudes who are bad at sex, which is more than enough reason to spread the word about it.

Hour of the Star

1985, Suzana Amaral, Brasil, 40th Anniversary

Based in Clarice Lispector’s classic novel, Hour of the Star paints a sadly familiar picture of internal Brazilian migration. The protagonist, 19-year-old orphan Macabéa, leaves the Northeast of Brasil for the big city, only to find that loneliness and unfulfillment follow her on the trip. Within the borders of Brasil, with its continental proportions, xenophobia is a historical reality, and Northeasterners customarily suffer prejudice, their cultural identity being tied to preconceived images of economic underdevelopment and often racially charged “slow-wittedness”. But any of Macabéa’s perceived shortcomings aren’t of her own making, and instead disclose structural injustices. She’s poor, but not for a lack of effort or work ethic; she’s insufficiently literate, but not for a lack of curiosity and willingness to learn, as she often asks questions so big in nature that others with formal education aren’t even capable of answering in good faith. Four decades later, it remains agonisingly relevant, despite how intimately personal the film appears at first.

Rome, Open City

1945, Roberto Rossellini, Italy, 80th Anniversary

Contemporary reinterpretations of Italian neorealist films often critique the movement’s portrayal of Italian citizens as innocent victims of fascism, claiming it exempts this imagined, naive populace of their ideological alignment. Some argue this historical indiscretion applies even to Rome, Open City. On the other hand, it’s hard to contest the film’s exceptional characterisation of Nazi-fascism’s atrocities. The pregnant Pina’s desperate chase for her imprisoned husband, which culminates in her death in the streets of Nazi-occupied Rome, is a strong contender for the most tragic scene in Italian cinema. Anti-fascism takes many forms, and Rossellini’s classic film exemplifies this through its ensemble cast, in which rebels of all kinds are represented, from Catholic priests to Communist atheists. Rome, Open City is a salutation for the many courageous souls who sacrificed themselves to resist Nazi occupation, and in the author’s eyes, that will always be more than enough to justify watching it.

Heat

1995, Michael Mann, USA, 30th Anniversary

Three decades have passed, and heist movies are still playing catch-up to Michael Mann’s masterpiece. Heat is the elephant in the room for any aspiring crime epic: it must be addressed, whether as an inevitable source of inspiration, or an artefact to reject and deviate from. The film is brimming with kinetic energy that can’t simply be stored away, it must be released - once the events are set in motion, not even the script itself could contain the eruptive power of Heat. De Niro and Al Pacino’s long-awaited on-screen encounter surpasses all expectations, and their game of cat and mouse is intoxicating. The genre-defining bank robbery sequence inspires more than just awe - it inspired real crimes, proving just how deep Michael Mann’s film has pierced the collective imagination.

Seven Beauties

1975, Lina Wertmüller, Italy, 50th Anniversary

A black comedy Fascist Italy-Holocaust picture, starring a violent chauvinist, and directed by a Socialist female director of aristocratic descent. Within those entangled, thorny vines of contradictions, one of the finest Italian films of the 70s awaits. Wertmüller shares an X-ray vision of how the vermin of fascism grew within the belly of her homeland, and her political tact is only outmatched by the audacity of her absurdist approach. Make no mistake: Seven Beauties is an offensive film, with imagery that can be outright morally abhorrent for some - from nauseating sexual assault to piles of corpses in Nazi extermination camps. This odd story locks the audience in a cage with the loathsome misogynist Pasqualino, throws away the key, and forces the viewer to witness his narcissism corrode even the steel walls surrounding him. No act is too despicable, and a new low is always awaiting, for physical survival is all that matters to Pasqualino, and any shred of principle can be negotiated away, despite his archetypical obsession with “honour”. One of the most bewildering pieces of political satire ever produced.

To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar

1995, Beeban Kidron, USA, 30th Anniversary

A queer cult classic, and arguably the first mainstream Hollywood film to recognise drag queens as performance artists. This road trip movie sends across America a trio of protagonists who act as fairy Godmothers in drag, their magic touch unlocking the repressed desires of a small town populace. Some terminology is certainly outdated, particularly the film’s description of gender identities, but its palpable sincerity hasn’t aged a day. Every beat evokes the intended response: every joke lands a laugh, every wholesome moment incites an “ownnn”. To Wong Foo covers masculine icons of the 90s in make-up and dresses, but laughs at the expense of no one except for racists, homophobes and misogynists. Though the film isn’t the most comprehensive depiction of drag as an art form (and it would have been nice to see the drag characters have their own romantic fulfilment), it brings to light the sense of empowerment and the strong community bonds that drag culture nurtures. Despite its clichés and shortcomings, To Wong Foo remains an underrated feel-good 90s fairy tale.

Forever a Woman

1955, Kinuyo Tanaka, Japan, 70th Anniversary

Tanaka’s feature is a touching portrait of Japanese poet Fumiko Nakajō’s unfairly short life - an unhappy mother of two who married the wrong man, and loves someone that she can’t be with. The film is a harrowing tale of remarkable talent recognised too late, and how the heartbreaking effects of breast cancer slowly injure Fumiko’s self-image as a woman. There’s no rush here, and the central events are built up so patiently that viewers might double-check if they’re watching the movie sold by the synopsis. The pacing is appropriate, since Fumiko herself never develops any desperate form of morbid urgency, and lives her final days with the same quiet appreciation for life as ever. Though not an easy watch by any means, the melancholy is intertwined with the sparse, yet precious joys that Fumiko finds in her last days - from dipping her feet in a puddle of water to feeling the warm touch of another. A lovely work that matches the tenderness of the poet it depicts.

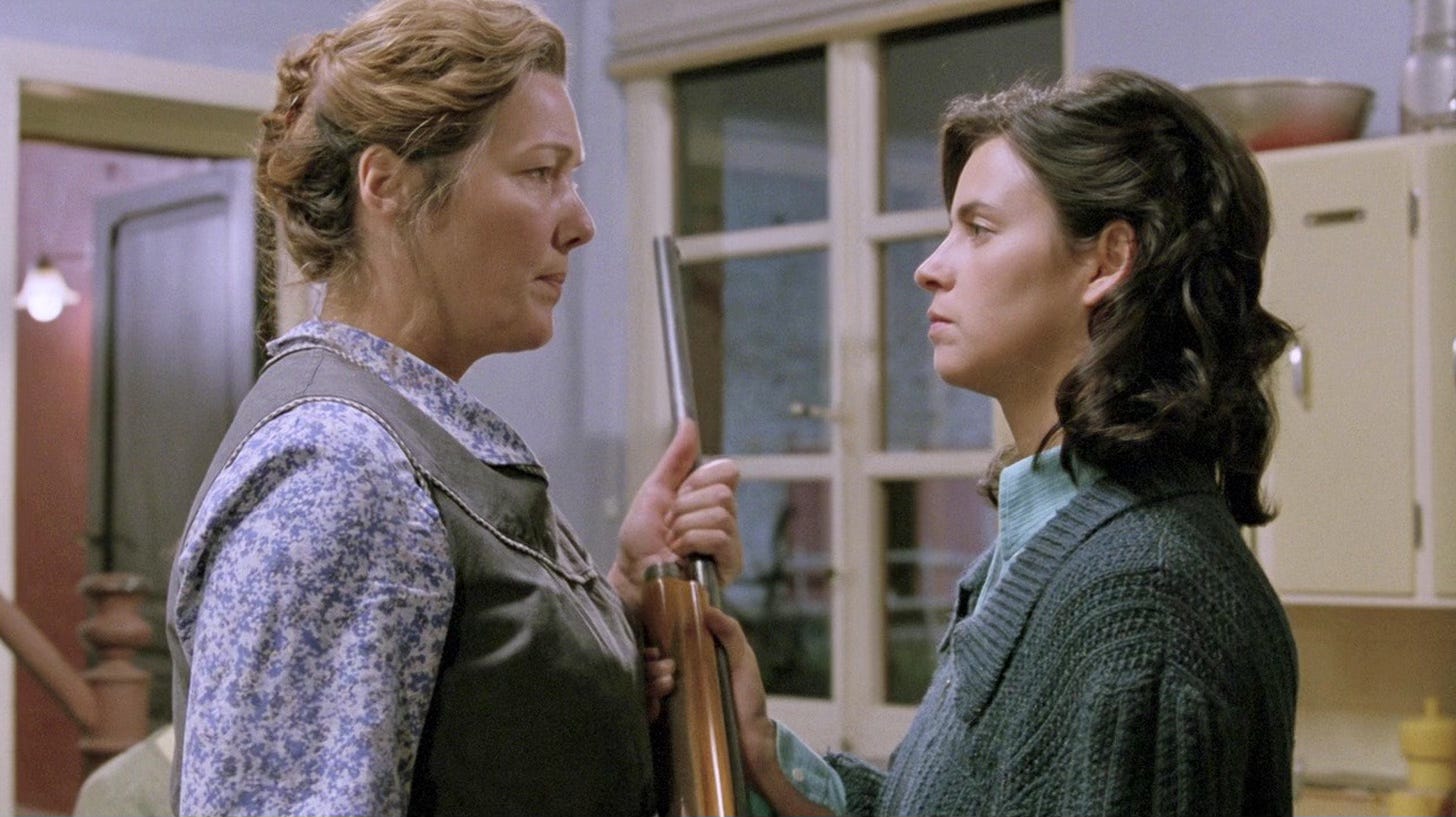

Welcome II the Terrordome

1995, Ngozi Onwurah, United Kingdom, 30th Anniversary

The first independent feature film directed by a black British woman, and one which still feels unmatched in its fury. A nihilistic vision of a future disfigured by apartheid, in which black bodies hold no distinguishable value to those in power, and which sounds less like science fiction the longer you speak about it. To borrow a term from another bleak sci-fi property, the Terrordome is a grimdark world, and Onwurah doesn’t hesitate before proposing violent insurgency as the only way to disrupt it. The film’s unapologetic answer to racial subjugation might still harm the sensibilities of white liberals who “don’t see colour” today, so it’s impressive that Onwurah put forward something this rebellious in the 90s. In Welcome II the Terrordome, the most venerated heroes aren’t the enslaved peoples who broke free in cathartic moments of victory, but the ones that chose death over servitude in the first place, those who walked into the ocean, chains and all.

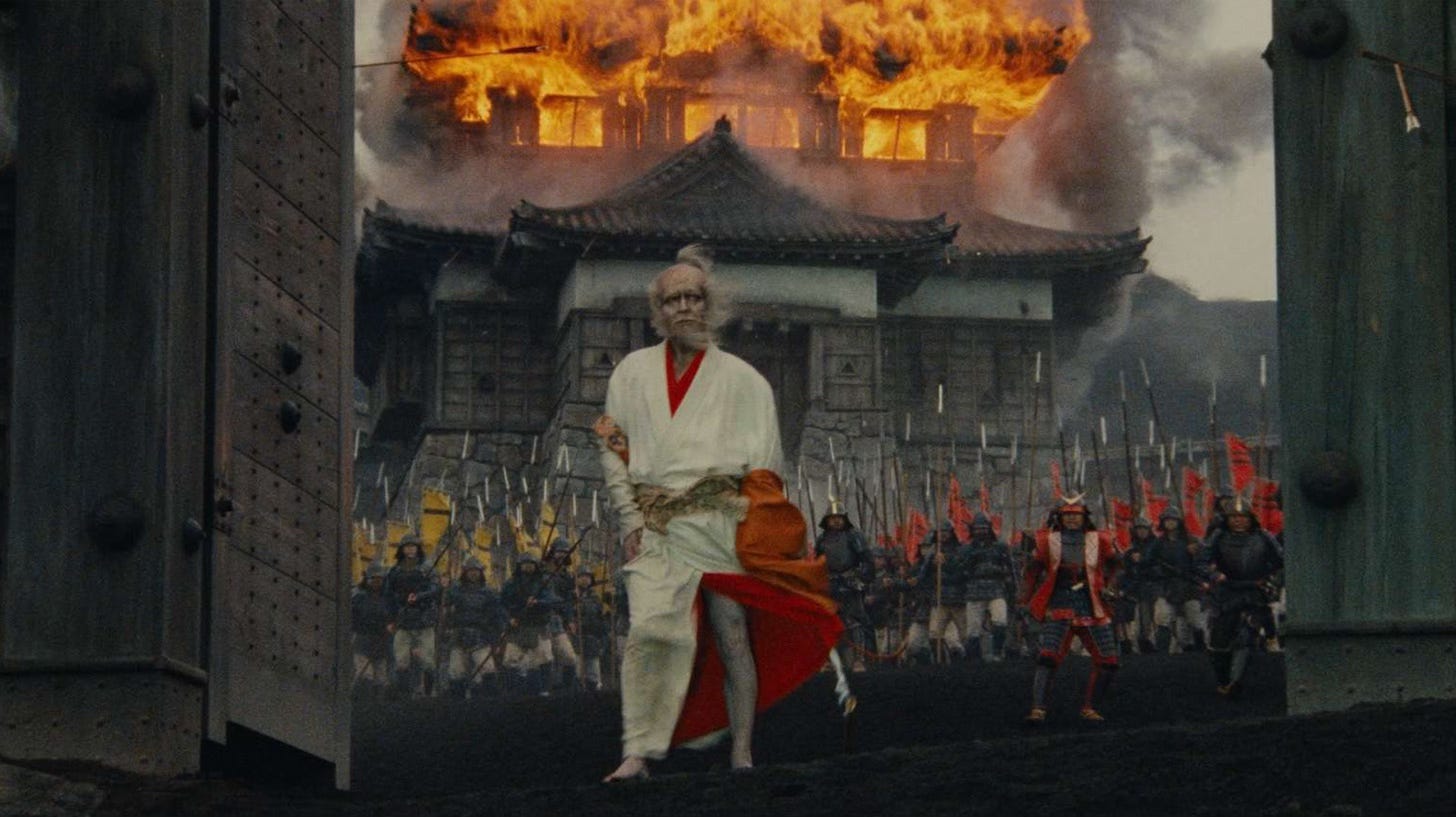

Ran

1985, Akira Kurosawa, Japan, 40th Anniversary

This Shakespearian epic lives up to the playwright’s notions of family drama and betrayal. The colours in Kurosawa’s film feel like a revolutionary iteration of something so regularly taken for granted, as if the filmmaker reinvented colour cinema in the 80s. Kurosawa’s signature sense of movement within stillness is present here, in a mise-en-scène bursting with smoke, wind, blowing leaves and rain. Between the clashing hues of massive opposing armies massacring each other, the film still finds the occasion for silence that feels deafening. The narrative’s moral spectrum is just as rich in saturation, and never stops interrogating the viewer. Is betrayal really always unjustifiable, or are there exceptions? Ran is a Japanese classic, and somehow more visually breathtaking than ever.

Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!

1965, Russ Meyer, USA, 60th Anniversary

An accidentally feminist classic about women whose hierarchy of needs consists of little besides good fights and fast cars. This exploitation film has been rightfully reappraised after its initial commercial and critical failure, and its visionary portrayal of gender roles has now been amply recognised. Three female nightclub dancers drive across the barren Californian desert, unleashing rage and unfiltered violence wherever they can, little pretence required. Barbarism for barbarism’s sake, the good ol’ Americana special. Totems of heteronormativity are periodically attacked: the trio brutalises an unimaginative heterosexual couple for seemingly no reason other than amusement. Tura Satana’s Varla is one of cinema’s greatest villains, whose utter disregard for life is stupefying, each of her feats of sadism turned into a hypnotic focal point you simply can’t look away from. In Faster, Pussycat, men are subjected to these cruel women’s whims, their bodies and very lives belonging to their illegible intentions - which are mostly murderous, of course. Leather, sports cars, and an unprovoked killing spree. Great film.

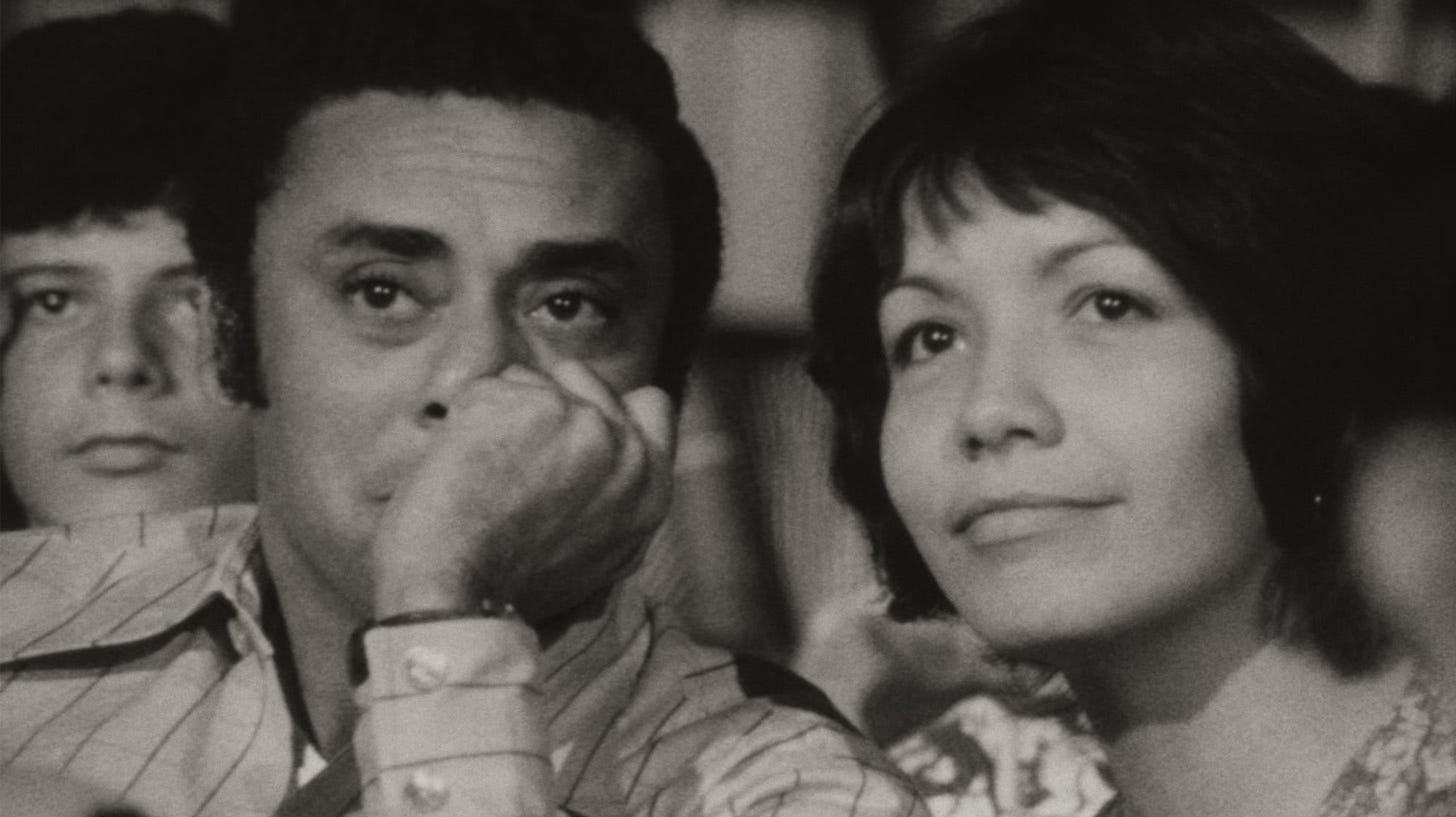

One Way or Another

1974-1975-1977, Sara Gómez, Cuba, 50th Anniversary

The first feature directed by a Cuban woman is a down-to-earth report of what follows Revolution, shot among those who have to live in its aftermath. This romance follows a female teacher attempting to educate marginalised children, as well as her macho boyfriend, who doesn’t understand her need for independence. The spectacular scenes set in factory union assemblies display how factory workers democratically discuss communal justice, and imagine entertaining conflicts such as “how would a Socialist society punish a man who skipped work to have sex with his lover?”. Gómez’s perspective is exceptionally nuanced, and her post-revolutionary tale doesn’t promise the disappearance of all injustices, instead making the case that progress can only be achieved through continuous fighting for intersectional solidarity. An amazing debut, and sadly her only feature.

Mad Max: Fury Road

2015, George Miller, Australia, USA, 10th Anniversary

George Miller’s magnum opus is a delightful embrace of cinema’s visual spirit, as the Australian filmmaker proves that a gorgeous canvas is not only a medium, but an end unto itself. The film’s compelling narrative, although jam-packed with quotable lines of dialogue, relies strictly on visual developments to advance through the storyboard. The bonds between characters grow through easily missed details, like Max gifting a boot to Nux once the two enemies become allies, or the silent operational sync up that signals Max and Furiosa’s newly found friendship. When the characters learn that “The Green Place” doesn’t exist, they understand they must fix a broken world with their own hands - there is no planet B. As the years go by, it becomes more and more sensible to affirm that Mad Max: Fury Road is, undoubtedly, the greatest action film ever produced.

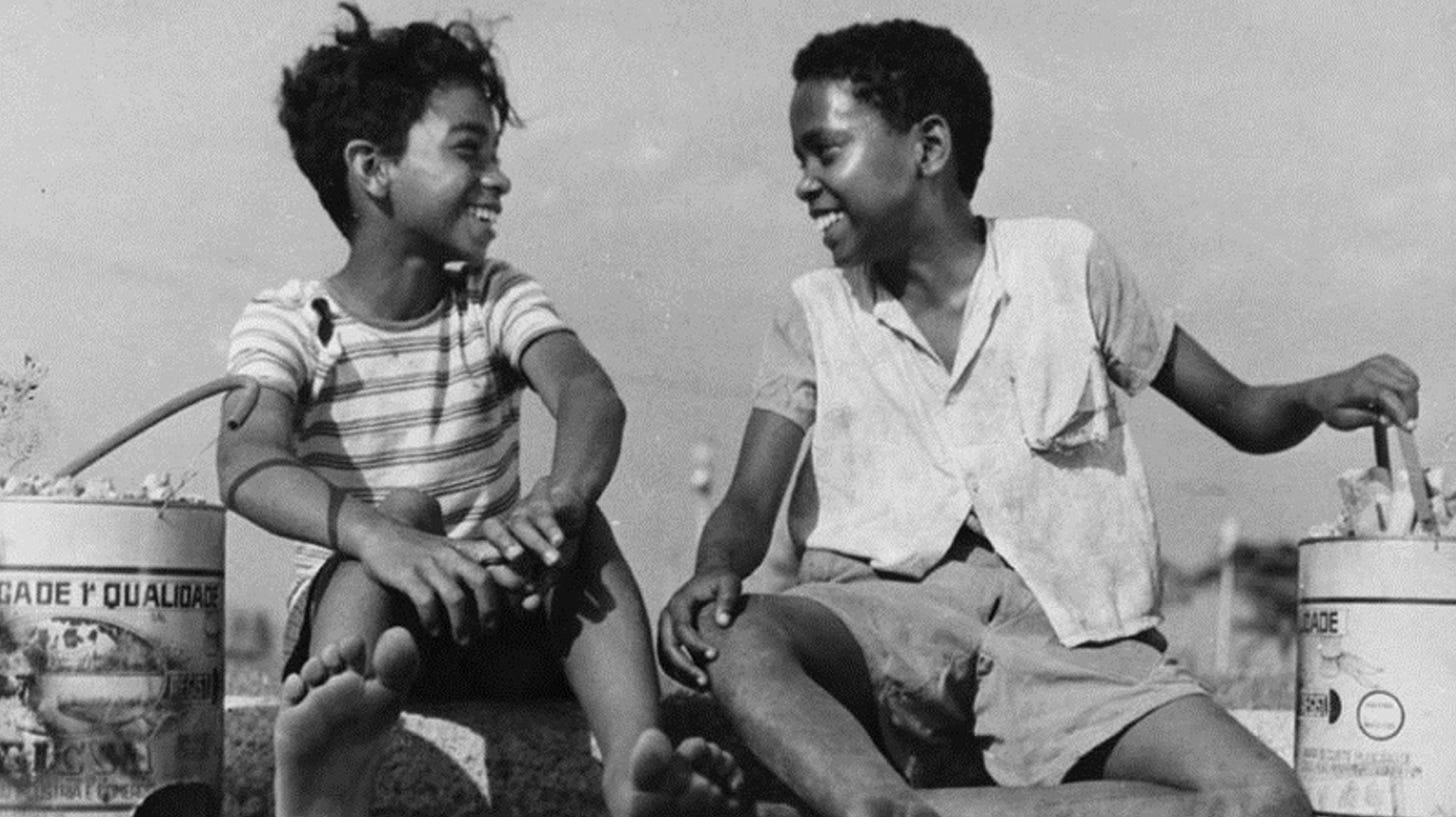

Rio, 100 Degrees F°

1955, Nelson Pereira dos Santos, Brasil, 70th Anniversary

This 70-year-old classic still feels fresh, which is great news from a cinematic perspective, and disconcerting news for Brazilian society, which has changed so little since the film’s release. What gives Rio, 100 Degrees F° such a sharp bite is the juxtaposition of major touristic destinations like Pão de Açúcar and the poverty that is invisible in the postcards. From structural racism to precarious urban development, the social frailties remain largely the same, as do the people’s choices of coping mechanism: samba, football, and the thrill of scamming naive gringo tourists. This visionary film preceded the Cinema Novo movement, Brasil’s response to Italian Neorealism, and similarly featured non-professional actors, themselves members of the unrepresented working class. Giving voices to the poor was hardly in the interest of a reactionary state, and the film was censored by the Brazilian government due to its excessively “negative” depiction of Rio de Janeiro. Nelson Pereira dos Santos, a known Communist, gave central attention to life in the favelas, and Rio, 100 Degrees F° is Brasil as experienced, or rather, survived, by the most vulnerable. In other words, it’s exactly the film that needed to be made in 1955, and still a must-watch.

Antonia’s Line

1995, Marleen Gorris, Netherlands, 30th Anniversary

This Dutch lesbian feminist fairy tale holds an uncontainable love for life. There’s something so invigorating about watching Antonia’s magnetic presence undo the patriarchal knots within her rural village, reshaping them into bonds nourished by mutual empathy and solidarity. From single motherhood by choice to Nietzschean nihilism, the range and number of subjects that Gorris addresses in under 2 hours is noteworthy. In Antonia’s matriarchal community, so many forms of affection and self-expression become possible, from elderly friends with benefits to lesbian couples raising STEM child prodigies. It’s endearing to see it all grow, and just as sad to see Antonia’s colourful flock diminish, as beloved characters grow old, and new generations arrive just as hungry for life. That’s not to say the film shies away from ghastly episodes, as themes like suicide and sexual assault are also discussed, but it’s precisely because it doesn’t conceal the awful aspects of living that Antonia’s Line feels like such a candid ode to life.

Right Now, Wrong Then

2015, Hong Sang-soo, South Korea, 10th Anniversary

A film about chance encounters, in which every word spoken is a step taken before arriving at a fork in the road. Ten years later, the 2-part structure of Right Now, Wrong Then still feels special. Hong Sang-soo’s style divulges a blend of sadism and self-flagellation - conquering the audience’s disbelief with such masterful handiwork, then puncturing it rather arbitrarily with jarring zooms. It’s like destroying an intricate sandcastle hours before even leaving the beach. The Korean director’s dinner table scenes are emblematic and always rich in possibilities, capable of switching from poetic exchanges to awkward disasters in the span of a minute, and Jung Jae-young is the perfect medium for this unpredictable tone. But no one can quite do it like Kim Min-hee, with her stares that can read as reserved, enamoured or barely tolerant, as if one wrong word or cup of makgeolli away from exploding. It’s difficult to estimate how many equally wonderful performances by Kim Min-hee haven’t been robbed from audiences, as the actress has been blacklisted from mainstream South Korean cinema since the reveal of her affair with Sang-soo. The extramarital incident is, of course, mirrored here (as in many of his films), and characters are positioned as surrogates for the filmmaker and the lead actress. Right Now, Wrong Then is a lesson in auteur cinema.

Vagabond

1985, Agnès Varda, France, 40th Anniversary

A story that begins with the protagonist’s frozen corpse occupying the frame, dirty and forgotten. Mona Bergeron’s life is remembered only through the documentary-esque testimonies others have to share, though none of them encompass the entirety of who she was, as they all knew her only for brief moments, and their words are often unkind. Varda’s film asks sympathy for a character driven by a restless need to move forward, devoid of a place that can make her feel at home, and shunned by a society for which she isn’t “productive” enough. Though it doesn’t shy from showing horrific events, it also commemorates the physicality of pleasant human connections - sharing food with a sympathetic stranger on the road or getting drunk with an old lady who finally feels seen as a person. Sandrine Bonnaire lives in the skin of one of cinema’s most complex characters, whose suffering is always difficult to witness, and whose flaws are just as hard to understand. Spectacular film.

Full List

Xala, 1975, 50th Anniversary

Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, 1975, 50th Anniversary

The Cave of the Yellow Dog, 2005, 20th Anniversary

Angel’s Egg, 1985, 40th Anniversary

BloodSisters: Leather, Dykes and Sadomasochism, 1995, 30th Anniversary

Hour of the Star, 1985, 40th Anniversary

Rome, Open City, 1945, 80th Anniversary

Heat, 1995, 30th Anniversary

Seven Beauties, 1975, 50th Anniversary

To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar, 1995, 30th Anniversary

Forever a Woman, 1955, 70th Anniversary

Welcome II the Terrordome, 1995, 30th Anniversary

Ran, 1985, 40th Anniversary

Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!, 1965, 60th Anniversary

One Way or Another, 1974–1977, 50th Anniversary

Mad Max: Fury Road, 2015, 10th Anniversary

Rio, 100 Degrees F°, 1955, 70th Anniversary

Antonia’s Line, 1995, 30th Anniversary

Right Now, Wrong Then, 2015, 10th Anniversary

Vagabond, 1985, 40th Anniversary

Great write-up. They were playing Angel’s Egg in a theater near me and I wish I saw it.